You are receiving this because you have subscribed to Daniel Firth Griffith’s, or Robinia Institute’s, or The Wildland’s email newsletter or Substack, which are, today, one and the same. Welcome.

If you enjoy this content, if you find it meaningful to you, we encourage you to become a paid member for $3/mo! With a paid subscription, you get access to all of my FOUR published and award-winning books (digital and audiobook versions) and so, so much more! It may be a cup of coffee for you, but it is the nourishment that keeps up alive, and we are so very thankful!

Listen on Apple or Spotify (but come back here to converse about it all…)

Episode Description

Picture this: a serene waterfall cascading over rocks, a herd of buffalo roaming freely, and the profound beauty settling in the simple acts of giving without expectation. That's where Harmony begins our journey in this conversation, using these powerful symbols to set the stage for a deep exploration of connection, identity, and reciprocity.

Harmony Cronin, our animalistic friend, shares her profound insights on death, gifts, and the metamorphosis of life reincarnate that bestows upon us Earth's gift of animacy.

We explore how the internet can bridge geographical gaps while also destroying the very essence of life. We navigate the knots of virtual communication, the discomfort of seeing oneself on screen, and the surprisingly beautiful connections forged through something as simple as a cold email.

As we venture further, we tackle the intricate dance of personal identity in the digital age. The anxiety of condensing multifaceted lives into bios, the disconnection it reveals, and the ancient wisdom that we've strayed from. We confront the societal expectations that force us into boxes, contrasting them with more holistic, kincentric views of identity. We also discuss how courses like Sacred Ecoliteracy can help us break free from these constraints and reconnect with our surroundings in a meaningful way.

Our conversation takes a profound turn as we reconnect with animals and nature, emphasizing respect, humility, and the deep-seated animism within us. We contemplate our perpetual indebtedness (a gift of debt) to the natural world, the philosophical recognition of animism.

The episode wraps up with reflections on simplicity, ancestral wisdom, and cultivating a responsible, appreciative way of living in harmony with all life. From the Buffalo Bridge project and cross-cultural connections to the importance of recreating ceremonies and honoring lost cultural legacies, this episode is a heartfelt invitation to embrace interconnectedness in every aspect of our lives.

Key takeaways:

The concept of animism challenges the dominant worldview that separates humans from the rest of the natural world.

Embracing animism can be a transformative experience that deepens our connection to earth: we are in and of her circle.

The death process is metamorphosis.

Reconciling with the death that feeds us is essential for the true integration of life.

Acknowledging and caring for all beings, including animals and plants, is crucial for a sustainable and inclusive way of living.

Dismantling colonial mindsets is crucial for developing a more holistic and reciprocal relationship with the natural world.

Participating in sacred and ceremonial practices and living in alignment with one's purpose brings a sense of wholeness and wellness.

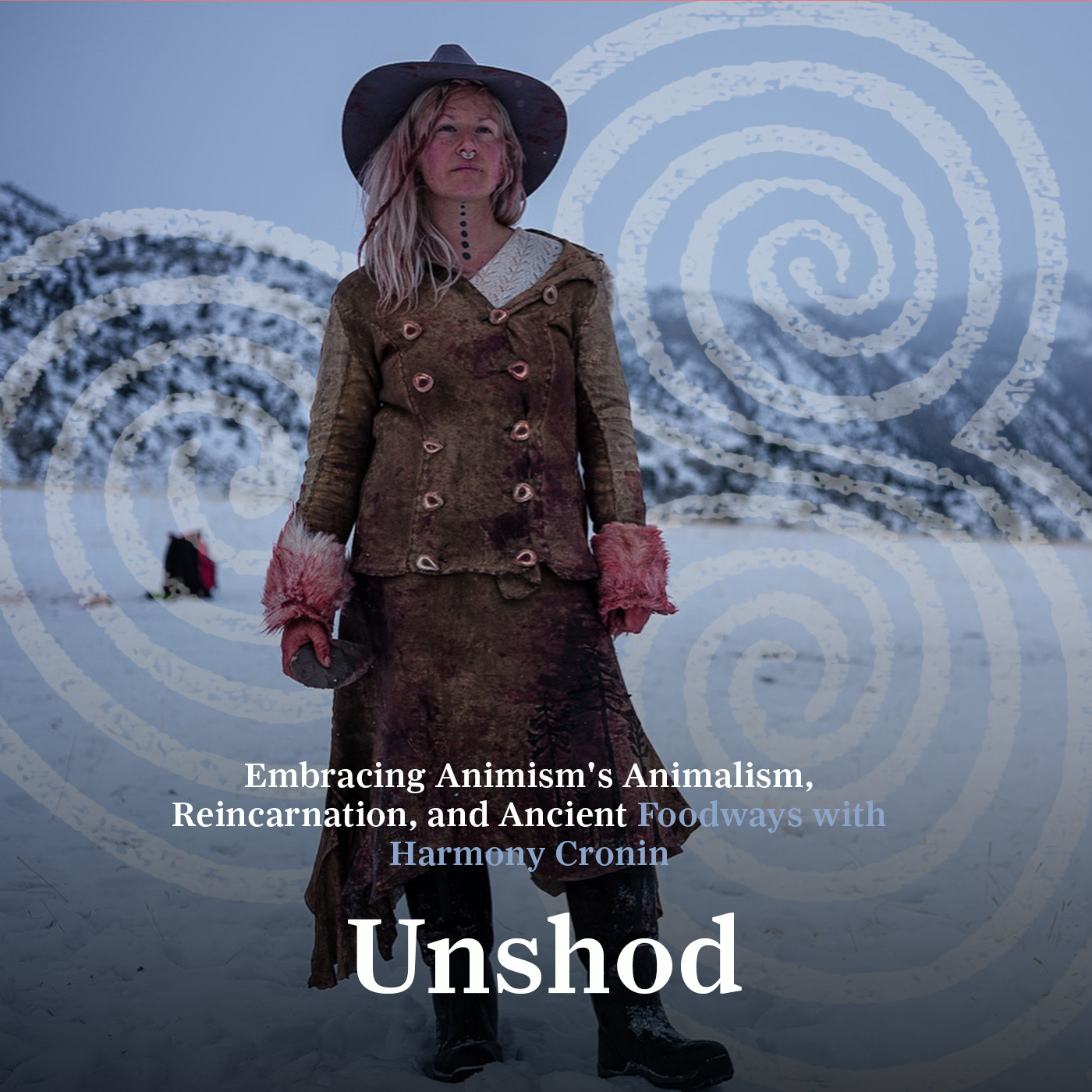

Harmony Cronin is an Animistic Apocalyptic Viking Warrior princess dedicated to keeping Ancestral Traditions alive. Shes a bit of an Elven Madmax biker butcher mystic and a believer in the Church of Roadkill. She’s an industrial age Magpie inspired Scavenger, a huntress who believes in taking care of the animals first and foremost, a recovering urban activist, and aspires to be a Mountain Peasant. She is a founding member of the Buffalo Bridge Project, hosts a Women’s Hunting Camp, and now runs a small folk school in Western Washington called Gathering Ways. She writes on Substack at The Raven’s Cottage.

Conversation Chapters

0:00 - Introduction

4:56 - Exploring Identity and Connection

19:27 - Deepening Connection Through Animal Communication

33:08 - Responsibility and Reciprocity in Animism

44:03 - Cultivating Responsibility Through Connection

55:28 - Simplicity in Everyday Sustainability

1:09:22 - Navigating Ancestral Guilt and Responsibility

1:15:36 - Embracing Simplicity and Ancestral Wisdom

1:22:59 - Embracing Simplicity in Connection

1:37:30 - Material and Spiritual Connection Through Animals

1:44:55 - Recreating Ceremony and Embracing Connection

1:55:11 - Buffalo Bridge and Cross-Cultural Connection

Conversation Transcript

Harmony Cronin: 0:00

May the buffalo keep you safe. May the buffalo keep you warm. May the buffalo wrap you and remind you that we are waterfalls of giving.

Harmony Cronin: 0:19

And it goes on. But that line may the buffalo wrap you and remind you that we are waterfalls of giving Right. And there it is. It's like the waterfall just pours. It doesn't expect the water to come back up at some point, it just keeps pouring, and pouring, and pouring. Um, is there a way that I can make my face disappear so I don't have to?

D. Firth Griffith: 0:56

there should be, why not? Um, let me see, I wonder. Yeah, I, I usually put something over my own face on my screen.

Harmony Cronin: 1:13

So you can always just like oh, I know it, let's see, maybe I could just like put a. I wonder if I could put a book, or something on it.

D. Firth Griffith: 1:17

Yeah, sometimes I just open up a blank like Microsoft word document and then I just oh a digital page.

Harmony Cronin: 1:24

Got it yeah. I'm not used to doing. I've only done a handful of like internet interviews, so this is all new to me.

D. Firth Griffith: 1:33

Yeah, if we had our druthers, I I'll tell you. Um, all of our equipment for podcasting and interviews is physical and mobile and, uh, we had long dreamed about doing in-person podcasts and we do do that sometimes when we have the complete privilege and pleasure to sit with people. In actuality, sometimes digital is all we have. Is your face covered.

Harmony Cronin: 1:57

Yeah, my face is covered. It's good. I am singing the praises of the internet because I get to listen to like my elders speak, even though I live in, you know, Port Townsend, Washington, like in a little wagon. It's just pretty miraculous to have your elders like anytime you need to listen.

D. Firth Griffith: 2:16

Yeah, that's a really, really interesting point. It's like in the world where we could travel. Travel sometimes feels to be a large burden to the thing that we actually need to do To be in place to sit, that sort of thing. Okay, harmony, thank you so much for being here. I reached out to you in a cold email, which I hate doing. It's like one of my biggest pains and fears in life, like cold calling and cold emailing people. I hate it because it feels like instantly we have to form a connection, and I hate that. I don't think connections really ever formed in instantly, maybe like an intimacy can be shared in the soul instantaneously, or like a particular spark can draw you into a location, but like friendship happening instantly over a cold email is not something I'm comfortable with, and so I just want to thank you for allowing the cold email to pull you in, to let us sit together and unfurl what this conversation has to give to us. So thanks for being here.

Harmony Cronin: 3:22

You're so welcome. Your cold email was beautiful and well-written and there was something in your articulation that was different than other cold emails I've gotten. And then it immediately made me go into your kind of your work and like what you do on social media and I was like, oh okay, there's a kindred spirit. So there was that spark almost immediately.

D. Firth Griffith: 3:43

That's really interesting. So there was that spark almost immediately. That's really interesting. Well, let's, I mean, one thing that I find really interesting about life is like the it's. It's simultaneously emergent and entirely ordained, and maybe that's the wrong word, but I'll use it for now, right after reaching out to you, and maybe this had something to do with it, and so I hope I'm not pushing into an issue here. Um, but you, you write on Substack and I followed you and really learned about you actually through.

D. Firth Griffith: 4:10

I don't know if this is a mutual friend or if this is an unknown supporter of your work, but Haddon Turner, actually from the UK, posted on Substack about your work and because he had recently written an article about re-learning to love the beautiful handmade things again in life.

D. Firth Griffith: 4:28

That's what the article is about, as I understand it, and he linked to your organization, your community, that I think we'll talk about, on this episode called Gathering Ways, if I understand the name, and I just went down a rabbit hole.

D. Firth Griffith: 4:43

I mean, I felt like I just I jumped straight into understanding you and getting to know you and looking at the courses that you guys offer and the opportunities people that you provide people to really conversate with the land around them. But I want to bring up this issue of like bio. You know, like I saw it right after the fact that you you posted on Substack about how hard it is to fit your life into a box full of words, not meaning and other things. So I want to open this up with a really strange conversation about, like who we are, how we understand ourselves, how, maybe in the digital world, we are forced to represent ourselves in like a cold email sense, like instantly upon meeting you. This is the paragraph that defines my life. Now we understand each other and there's a falseness there. So I want to open this conversation up I have no direct question and then see where it goes. Yeah.

Harmony Cronin: 5:37

Yeah, yeah, I did write that sub stack. It wasn't just from your cold email. I've been getting a lot of podcast pitches lately and I just have struggled so much with writing bios and it has brought up so much. Well, first anxiety, because how do I sell myself Right? And then the anxiety of like, why am I even thinking about selling myself and how do I represent myself. And then the anxiety about, well, why do I need to represent myself? When in history have we ever represented ourselves?

Harmony Cronin: 6:10

And this, I feel like that in itself is a whole new way of orientating ourselves to our community and our world. And it feels utterly wrong for me to dictate who I am. It's like. It's like I can't even understand how I'm supposed to do that, because immediately, what that does is put me out of my body in someone else's eyes, looking in at my life, which is what your community is supposed to do Like.

Harmony Cronin: 6:39

I think that that's the proper function of community and not just the human community, but the plant community and the wind community and the water community to see you through the stages of your life, who you are and how you are in the world, and then reflect back to you who you are or be in a platform where I mean, how do I on like a podcast like this, how do I have the plants and the animals that I tend and the waters that I tend and the soil that I tend? How do I have them write my bio for me? That's what I'd like to do, because who the fuck? I have no idea who I am. I just live my life and I am myself and I continue on my path, praying for guidance along the way, and I hope that I do a good job and I work to do a good job. But I think that our bios, who we are should be reflected by the ones around us. And it's just a scary I think it's actually it's. It brings up a lot of grief for me. For me, like tears are kind of close to my eyes actually that we're in a timeline right now where so many people that's not only what they do that's like encouraged and one of the ways towards supposedly making something of yourself is to self declare who you are and what your work is in the world. And to me, that just like it's such a symptom of of disconnect and of our broken village-ness, and I mean so many things that are a consequence of, uh, what we've been handed down.

D. Firth Griffith: 8:20

Well, it is interesting, um, so you provided a bio. Um, there provided a bio. I don't want to lose what we just did, but I want to unfurl this a little bit deeper. It is interesting things that you don't know happening on this end. So you sent a bio, your best attempt, also your worst attempt, and it's fine in the modern sense and it's worth grieving about in a very ancient sense. It's fine in the modern sense and it's it's worth grieving about in in in a very ancient sense.

D. Firth Griffith: 8:50

And, uh, I believe the first couple of words was animistic, viking or something like this. The word animism it's wonderful. I want to talk about that with you here in this conversation and and someone in the community, because what we do with this podcast is release, you know, the knowledge about a, a recording, a conversation previous to what's happening, and then people can weigh in and you know, maybe they know about your work and they can ask you a question that they've always wanted to ask or whatever it is. And we had two people comment calling you animalistic not animistic, but animalistic and at first I couldn't, I didn't, I didn't know if they were complimenting you or berating you. You know, know if they were complimenting you or berating you.

D. Firth Griffith: 9:29

You know what'd you decide? Unfortunately, they were berating you, but I saw it as a compliment. You know, immediately I was just like wow, wait a second. How wonderful is that, you know, for for harmony to really actually see herself as, as an animal. But that's wonderful, because that's what you are Right, we are a wonderful mammal and, um, well, it's just these, this box, right and and and, and it seems to me like this, this disconnect that modern humanity has in this industrial I hate to call it a complex as it's if it's as, if it's complex, but it's. It's a complicated system that we are surrounded by, that's grieving over I, I do like that, that phrase that you used. It is a deep, deep grief, but it forces us into this box, to be understood as a singular thing, um, which we know isn't true. We know this, isn't true I. I wonder, um, we teach a number of courses.

D. Firth Griffith: 10:19

One is called sacred eco-literacy and I'm sorry, I feel like I'm doing all the talking here. I have no intention of that. We'll get to you soon, I, and then I'll be quiet. But we teach this course called sacred eco-literacy and it always opens up in a ceremonial circle, a gathering, and I ask all the students we just taught it last weekend and there was about 30 students and I ask each student what is their name and why they are here, and inevitably they talk about themselves in a very bio-esque sort of way and then I say, okay, we're going to do this again, but now I don't want to know anything about you or your name, but I want you to tell me about the land that communes with you, inside of you, right? So talk to me about the birds and the rivers and the wind and such.

D. Firth Griffith: 10:58

There was 10 people out of 30, maybe nine to 10 people that had broken out into tears the minute that they got to introduce themselves, not with their name, you know, daniel or Harmony not with what they do or who they are or where they are, but the land, the kinship that they share, that makes up their bodies. And people talk for a minute, two minutes, you know, about things that they've never enunciated, never pronounced into their life, as an aspect of their life. And at the end of that moment we still had a whole day's worth of time together for the course, for the continuing of the ceremony, the sacred ceremony. And uh, and I looked up at him and I said, um, you're done, you got it. You know, to a large degree, like you got what you came for. You know this reawakened sense of kinship. So, animal, animalism and animism I want, I want to play with that. What do you think? Are you animistic or animalistic? A?

Harmony Cronin: 11:48

disconnect and of a severance from um, the living cosmos and the living world, right, and you like you can trace this and when it happened in language through etymology, and so, like a word like animosity, right, also shares that same root word, anima, which also has to do with the soul, and I think it's so beautiful that animals have within them the seed of our soul, even etymologically speaking. And so animosity somewhere along the line got switched from meaning you know of animalistic characteristics to what it means now, which is something to be avoided, like animosity means aggressive or domineering or something like that. And so I like tracking those kinds of things in language, and usually you can track it to a very specific time in history when meanings really got shifted with things like colonialism, conversion to certain monotheistic religions, and so animalistic I would say I'm animalistic and I think it's a folly to think that you're not, and probably pretty dangerous too, because if you can agree to being animalistic and agree to being part of all of this and interconnected and in pace with it, then you can be truthful in how you are. But if you are an animal, which we are, and you're pretending that you're not and you have these kinds of mental gymnastics that come up with all the reasons that you're not an animal, then you're perpetuating certain things under a disguise, and right, yeah, I mean I could go on a bunch of different tangents with that one and I.

Harmony Cronin: 13:53

So I think it's just more truthful to say yes, I am animalistic. I think that's a beautiful thing. The animals that are in my life are so generous and so kind and so um, so generous and so kind and so um, so wise. I want to learn from them. I, it would be my pleasure to be animalistic. May I be so lucky actually to be animalistic. I like they're like some of my biggest teachers. So thank you for calling me animalistic. Whoever you, I do take it as like the greatest compliment.

D. Firth Griffith: 14:25

Yeah, and perhaps you grieve over their distaste for it. It's worth grieving about, I think, what I would like to do, and just for the moment. I rarely ask people for their stories and so don't feel like I'm asking you that now. But you have a lot of really fun stories, engaging stories, full of grief and pain and joy and everything in between, all the way from eating rats, which is a new thought to many people, an old thought to you, a wonderful thought to living in a true I don't want to call it a wild sense, but a true animal sense, living out with the world around us, as us, in the circle that we are in and of, with wolves and many other animal nation and plant nation life. And so I want to open up just a little bit of a moment for storytelling. I think story is so absolutely powerful. Whatever comes to mind, I'm happy to sit with it.

Harmony Cronin: 15:18

Yeah, I think maybe starting with the first door that started creaking open towards the animal world, that I can remember Well. Actually now there's one coming up now. When I was a little kid, my dad was a really devout Christian and so I grew up kind of in an evangelical Christian kind of household and he was pretty afraid of anything that wasn't within the confines of the church, and so I was maybe in third grade or something and I found this little it might have been a rat skull. Looking back, it was either a rabbit or a rat, and I kind of want it to be a rat because later on it's like the rat is like my totem animal or something. So I found this little rat skull and I put dental floss around it and I made a little necklace out of it and I wore it to school that day, so proud of my necklace, and of course, like all the kids were like ew, disgusting, that's gross. And I remember going in the bathroom and taking it off and like that was maybe one of the moments that the animism that children are born with like started to be shamed out of me, you know, and so I don't know I might've like hit it under the bathroom sink or something like that. And, um, I bring up my father, because during that time too, I was really into stones and sometimes I would tie a little stone on a necklace and I remember him saying take that off of your neck, we're not earth worshipers. And that has stuck with me all those years and he's dead now. Bless his soul. I love him so much and he taught me so much and the Christian stories have taught me so much too. And so, yeah, that rat skull around my neck was something. Something was alive in me then and then it kind of got pushed to the side for years, years and years and years. Until much later in my life.

Harmony Cronin: 17:23

You know, I was a activist in the city and really angry about a lot of the things that were going on in the world and didn't really know how to navigate. I was really full of anger and going to protests a lot and all of that sort of thing, and I was vegan as a response to the anger that I felt about industrial farming and animal slaughter and all those. And so I was vegan for years and years. Um, and so I was riding my bicycle. I was a teenager maybe, or maybe I was 20 or something, I was still pretty young.

Harmony Cronin: 18:00

So I was riding my bicycle and it was dark and I rode past this roadkill squirrel and the roadkill squirrel. As I rode past, I heard the squirrel say something like if I was a dead human, would you just pass me by. And I stopped my bike. I remember so clearly just stopping, being like what the hell. And I looked back and I thought, right, if this was a dead human, would I just pass them. Like this is horrific, as all the cars are blasting past, nobody's paying attention to this life smeared on the pavement and I thought, oh my God, something is really wrong.

Harmony Cronin: 18:48

And so I had a plastic grocery bag and I went to pick up the squirrel and I couldn't even touch him. I was so afraid, I was like couldn't bring myself to touch him. I was so spooked out by death which now tracking myself. I mean, yeah, that death phobia is so real, especially with urban people. I grew up in an urban environment and death is just packaged in styrofoam and you never have to look it in the eyes, and but we eat it every single day. But then somehow we're able to say that you know, we don't want to participate in the death cycle.

Harmony Cronin: 19:27

And so I picked up the squirrel in the bag and I drove him home on my bike, put him on the handlebars of my bike and I remember sitting with him and with him in front of me out under the moonlight and and and going to touch him until I could finally touch him and hold him in my hands and I just remember the beauty, his beauty of the fur, and just the little whiskers and like little paws and little claws, and I remember being astounded just at the like perfection of this squirrel. I'd never been that close to an animal like that. We had dogs growing up and cats, but it was just. He was so other than and I don't remember, I don't I didn't really know how to skin animals or eat them or do anything with them. I think I might have cut his paws off to make earrings or something, and that was kind of the beginning of like, oh, people used to use every part.

Harmony Cronin: 20:28

I remember that kind of playing in my mind and I didn't know what that meant at all, and I buried him in the yard and we had a little squirrel funeral and that opened up the door towards picking up roadkill whenever I saw it and just really feeling that grief of like kill whenever I saw it, and just really feeling that grief of like, wow, somebody killed this being and then, most likely, kept driving. And now everybody's driving over it over and over and over. Just imagine if it was a woman that people are driving over, over and over and over. And why is it different? Because it's an animal. So we started burying roadkill in the yard and having funerals the women I was living with all kind of. We all started doing this together and it was really beautiful. It felt so good to get them up off the pavement and at least onto the dirt where they could or into the dirt where they could decompose, and so that that was one of my first experiences that I can remember of direct animal communication and direct animals animals teaching me something directly.

Harmony Cronin: 21:36

And this isn't like an abstract, like symbolic representation of animals teaching, like they're literally trying to speak to us, and it's not hippie, woo, woo, it's like it's real. And through many years of being with the animals and speaking with them and trying to listen, what I came to is, if you have a human in your life and if you treat that human like they're incapable of communication and you don't say good morning and you never speak to them at all and you treat them basically like they're just an automaton. And then all of a sudden one day you're like okay, let's see, um, are you, can you actually speak to me? And you approach them in that way. Do you think that person would want to talk to you? They might think you're a dick, right? They've spent you've spent your whole life treating this person like they can't communicate.

Harmony Cronin: 22:34

And I think that's how a lot of people approach this. Once they learn about animism or being in relation, they might have that kind of internal judgment of like well, they've never talked to me before and I've never heard them before, and so I don't know if I believe it. But I think that we have to go slow a lot of the times and make a case for ourselves and approach them in a way like I pray all the time for forgiveness. You know, cause I still have a really deep, um deeply conditioned in animus sea inside of me and I there'll be days where I forget that everything's alive around me. I forget that the plants I'm eating were alive, you know, even the animals sometimes.

Harmony Cronin: 23:16

And so I think that approaching in that way, that humbleness, and realizing that I spent most of my life treating these beings as if they're not alive and, even worse, that they were kind of my slaves, you know, forcing them to do what I want them to do without ever asking them or speaking with them or thanking them. And so there might be a little bit of a friction rub, um, when it comes to opening up, relating, and that's okay and it doesn't mean you're a bad person and it doesn't mean necessarily that you did anything wrong. I think it's just the times we were born into and it's not too late. But I just I would yeah, I would say that taking some time and accepting that not every plant you see or approach is going to be necessarily outpouring with their communication.

Harmony Cronin: 24:14

And also our bodies aren't necessarily made of the ones around us anymore. Right, the more you eat of right outside I'm like looking at the garden right now I see beans and corn and squash and greens right now and so the more we eat of the ones literally right outside our door, the more we're physiologically made of them, and then the more we're able to be calibrated to the way they communicate. And so I think there's like multiple threads here to pull on when we're learning how to be in true communication with the ones around us, and also being a vegan, right. So I hadn't eaten animals in so long, and so, of course, the like communication with animals was a little bit off. It was pretty faint at that point, but that squirrel really turned things around for me.

D. Firth Griffith: 25:02

Yeah, it seems like many of us are still clad in this dominant worldview of colonialism that like wants to be imbued with animacy but doesn't want the effects of it. Like we want to believe that the squirrel is animate but we don't want to stop and pick it up yeah, yeah, that, yeah, that was that just hit me.

Harmony Cronin: 25:22

I think think you're right and something that I've. Yeah, it can be really hard, because when you really start listening to the forest around you and to the waterways around you, a lot of times they're in a lot of pain and a lot of these plants and animals are actually suffering quite a bit, and it's not something you can ignore. Once you start hearing it, you know, and so I think you're right. Like people want this animacy, they don't want to feel so alone, they want the plants and animals to be able to communicate, and then sometimes, when you open up to that communication, it's fucking painful yeah.

D. Firth Griffith: 26:17

Well, I think, for the first time, you realize that you know there's this wonderful idea that we are all connected. It's like, yeah, indigenous people believe this, but I don't actually have to suffer through that idea of connection. And when I say suffer, what I mean is the grief and the pain, the glitter and the joy, the death and the blood and the metamorphosis that the death and the blood, you know, rejuvenates and restores back into the consumer. You know the willing, full participant in that cycle and the chaos. You know all of these things. It's a hard reality, I think, and I want to be clear and at the same time so unbelievably beautiful that it's so worth sitting and crying about.

D. Firth Griffith: 27:03

I think people like you and myself obviously you have your own way of doing it. I don't want to equate, but we lead, you know, field harvesting courses. You lead, you know harvesting courses and butchery and we have the pleasure of bringing people out into a world where they get to truly actually, maybe for the first time, participate in that death process. Right, and I think a lot of people and I I this is a question for you I want to know your experience as a, as a leader in that process, as a escorter maybe is a better word through that process for people. But I think they come preparing for death you know that they're they're, they're psyching themselves up, they're trying to reconcile that their life involves death and they, and maybe they come to these experiences, gathering ceremonies, courses, whatever they are expected to experience death truly for the first time. And I think what's always been surprising to me is it's not the death that is surprising to them, but it's the chaotic rebirth, the metamorphosis, the reincarnation of that life in that moment into something so much more real than death could ever be, in a very philosophical sense, a very distant sense, and they break down, covered in blood, whatever it is. They break down and I feel like they meet themselves for the first time. Right, because they understand.

D. Firth Griffith: 28:21

You know, there's this wonderful book, it's Till we have Faces, and it says at the end of it I'll ruin it for everybody. So if you're not interested in having the book ruined, to skip 30 seconds ahead. But it says how can we expect the gods to meet us till we have faces? And just thinking about, you know, till I have a face, till I recognize the face, do I really reconcile what my face looks like in the grief that having this face has imbued into the natural environment and all of these things, all the things that you're speaking about.

D. Firth Griffith: 28:48

But I wonder for you, as somebody who has the unbelievable privilege to escort people through this death, metamorphosis, chaotic rebirth process and learn about the true integration of life through life and all of this harvesting and butchery and art, weaving and everything else, I wonder what do you experience as people, modern people with this dominant worldview that we want to believe is animate, but it's not? We're not willing to go that far. We want to, but we can't. What is the first moment of actually tasting that animacy like to the people you get to spend your days with? Wow?

Harmony Cronin: 29:29

it's a rich question. Yeah, I've seen. I would say the the. What's swimming up at me right now from the memories is seeing people with a knife in their hands killing their first animals. And that initial well, it's not an initial act, because I think this starts way before the actual killing of an animal, but that the movement of making the decision, taking responsibility for the death that you're creating by the act of killing an animal, right the, the deliberate decision and the confidence needed to make that decision when you're plunging a knife into an animal's neck, um, even if there's some hesitation in there that that upswelling of of decision transforms people, I mean mean that there's so many moments of transformation through the whole process. But I've seen I'm thinking of a few women right now in my mind of just absolutely, I guess, like right, it's like they are now honed into the knife edge like their way. They're being honed in to that like razor point sharpness and because we're participating in death all of the time, regardless of what you eat as a vegan, you're participating in death, and I mean arguably more animal death than someone who eats meat that they kill. And so we're participating in death and eating death all of the time, and I would argue that a lot of times we're not taking responsibility for the death that feeds us. And so that moment of stepping into taking responsibility and then literally looking death in the eyes, yeah, it transforms people forever. To see the light in an animal's eyes fade out and go wherever it is that it goes. Eyes fade out and go wherever it is that it goes. Um, and knowing that every time you put anything in your mouth to eat it, that's what you're eating, whether it's a carrot or a cow, um, and so the weight of that you know and I know that it can threaten to be too much for people that weight of like wow, this is what it means for me to be alive, is that I create death, and that can really be so heavy for so many people. Remembering like, wow, up until this point, how many animals have I eaten in my life or how many potatoes have I killed? Like, going back and back and back, and then, all of a sudden, you feel this responsibility and obligation to those ones that have died for us, and it it can almost break people.

Harmony Cronin: 33:08

But I think that something that I speak about in the course is that it's not. I don't think that this debt right Like, we want to think of it as like oh well, now I owe this animal something or I owe this plant something, but that cycle of debt is a very new kind of capitalistic formation. It's not to be repaid. I don't think that that's. The reciprocal relationship that we're trying to enter into is like now I'm in debt to you and now I have to repay your life. I think that it's not. It's not meant to be repaid. It's meant we're meant to be indebted, we're meant to be always.

Harmony Cronin: 33:50

Um, it's like the I don't want to say engine, but maybe that's a proper term. It's like an engine of reciprocity to be indebted, right Like in between humans too. If there's a human that I owe something to, it's not necessarily that I should pay them back immediately, because it keeps that link between us alive, actually, and we should always be indebted to the ones around us to keep those links alive and to keep informing us of how to live our days, like even right now. If I completely stopped eating and wasn't requiring animals to die or plants to die for me, even if I worked every moment for the rest of my life to repay the animals that have died for me. I could never right there's just like it's, so beyond my capacity to repay them. But I will use that to inform how I am and how I show up and like my prayers and what I work for in the world and what I speak about and how I carry myself, because that weight is there, so it's not meant to break us. It's meant to help us be stronger.

D. Firth Griffith: 35:05

Right, I think of memory quite often, and that's the image I'm seeing as you're speaking. This idea of remembering is like remember as two words, putting ourselves back together by those that built us. And I think animism like we're talking about this idea of animism being so easily understood philosophically and so hard to grapple with physically so hard to grapple with physically and I think you're speaking about this responsibility, this memory, these things that we carry with us, these wanting debts, these gifts that we give back and forth in this wonderful reciprocity. It is interesting speaking about words, reciprocus is the Latin root of reciprocity, right, reciprocus, and it literally means backwards and forwards simultaneously, like at the same time. Like you can't actually exist, like we can't scientifically or mathematically understand reciprocity, because it's kind of like the great circle, right, that we are in and of that life and is it enough? And that death is in and of, and that you and I, in this moment, are in and of, and so backwards and forwards simultaneously. It's like this re-memory where we dream backwards and we dream forwards at the same time. Right, we are the legacy of our ancestors and at the same time, I dream dreams that my grandchildren will walk in, and so it's just really interesting. But I think death allows us that moment, that harvest moment, like you're saying, with the knife in our hands.

D. Firth Griffith: 36:28

You mentioned earlier this idea of calibration. We've been calibrated by modernity, by industry, by the machine that surrounds us, by the machine that's eating us from the inside out, whatever phrase you want to use. We've been calibrated to understand our life maybe as being sacred, depending on the religion that we follow. Maybe it's not, but maybe it is. But that life is important as in it's distinct. But the calibration I think that happens is a recalibration like a knife's edge, like when you're honing it on stone or steel, and you're recalibrating that edge like you're not actually sharpening it, you're just recalibrating its point so that it goes perfectly dead. You know, dead straight.

D. Firth Griffith: 37:08

And I and I wonder how much of that process for people is not necessarily the shaving away of this idea, like the dismembering, but the remembering right, the recalibration of being forced in that moment to understand that animism is not, like you said earlier, like this new age woo-woo sort of like. Oh yeah, trees are living like human, but it's actually like no, we actually have to be responsible now for these trees and for our relationship with these trees. And so I wonder maybe this is worth investigating. I wonder if the reason that the dominant colonial worldview has such love and hate for the idea of animism love in the sense that we can approach it philosophically and hate in the sense that we don't ever want to approach it physically or in a real sense is due to the fact that if we did actually approach it, we would have to be responsible, not necessarily for fixing it or repaying the debt, but just responsible in the acknowledgement that we exist and it exists, and in that existing pain and joy exists simultaneously. What do you think?

Harmony Cronin: 38:18

Yeah, I've thought a lot about that. I think that you articulated it very well that the longing for animacy is there. And then, once, folks kind of peek behind that door and they realize, wow, if everything is actually alive and actually capable of personhood and consciousness, then yeah, then, and if these beings you know, many of them are struggling because directly because of human choices being made and I'm not even necessarily talking about climate change, you know, I'm talking about like very acute things as well, um, like toxins in the waterways and, um, things in the air that the plants can't wash off of themselves, that are affecting them Um then yeah, then you are responsible and I think that then it actually requires you to make some changes and it's scary to people. I've never really personally felt the like fear thing and I don't know if that's what that's about people. I've never really personally felt the like fear thing and I don't know if that's what that's about, because I've always just been like fuck it, let's just make big changes because it needs to happen, you know, but it does.

Harmony Cronin: 39:41

If it threatens somebody's stability, then and they're not quite ready to do it, or whatever it is, then I think there is a lot of fear there, um, because the change is necessary for everyone to be well, including the plants and the animals and the waters and all the beings, that those changes are big changes, I think, um, and that it should actually bring about some big deaths in your philosophical and physical life and all of those sorts of things. Like you know, I can think of some people in my life right now who they don't even want to hear about animal slaughter, right, they don't even want to hear about what I do, because even just the mere thought of an animal dying, even though they're all meat eaters, is too much to bear to even think about it. And so what does it mean? If you could, if you see it then with your own eyes. But then you have to ask yourself well, what are you protecting, lil? What are you vehemently trying to shield, and is it worth protecting?

D. Firth Griffith: 40:47

I wonder if it's a great question. I just wonder often if the reason we want to shelter ourselves from the death is because we don't actually want to reconcile that that death metamorphosizes, it reincarnates into our life when we eat it. And we don't want to also believe that the death process actually matters in the food that we eat, the nourishment, the life that it remembers into us, remembers into us. Because if I don't have to reconcile let's just say, the McDonald's hamburger, if I don't have to reconcile the method of that life's death, let alone its life of course, that's a whole other conversation, the same conversation, just for it much larger In words. Not meaning, If I don't have to reconcile that animal's death, or if I don't want to reconcile that animal's death, I don't actually have to start considering. Why am I eating it? What is it actually becoming inside of me? Right, and I can distance myself from that process.

Harmony Cronin: 41:40

It's kind of interesting, isn't it? I haven't thought about this until now, that distancing of the process and the responsibility is kind of part of this self-perpetuation of isolation. It's like we feel lonely, we feel pretty isolated right, it's a huge problem in our culture in these times but then if it's like we're looking for connection, then it's like, oh no, it's a little bit too big and a little bit too painful, like I want to isolate further and it's just kind of an interesting addiction. Wow, yeah, wow.

D. Firth Griffith: 42:19

Yeah, it's an addiction that also simultaneously allows us to slough off responsibility. Right, yeah.

D. Firth Griffith: 42:27

Speaking about my children, you know I'm thinking about the story that you so lovingly and kindly shared with us earlier about you being a child with a rat or rabbit skull on your neck. My wife and I, we have three children. We live in the middle of nowhere, about an hour away from anything, and we forage for a good majority of our food, if not harvest it, you know, on the land, meat that is. And, like you know, today we'll harvest a sheep and you know the kids will do it, and our oldest is six and they're very skilled at it, but in the same sense it's still very sacred to them. So it's an aspect of their life, but still being sacred. That's something that's very important that we talk about in the courses. I'm, as I'm sure you, focus on the idea of being at home, while simultaneously not negligent of the details of the care of the ceremony. But it's interesting because, like you know, we'll be having a meal, and I was not raised thinking like this. But we'll be having a meal, you know, and our three-year-old will ask, like who was this or who is this Is a much better question and she's three and she just doesn't know better from, like, a modern perspective, she doesn't know better. And also, that's, you know, you know it's Alejandro, one eye or whatever that is, and she'd be like, ooh, yeah, that tastes good and it's just like this level of connection that requires no terminology. Like, if I look at my three-year-old, her name is Sequoia, or bean we call her bean and I would say, oh, that's, that's called animacy. She would be like animal, what? That word doesn't make any sense. Right, you and I are trying to relearn this concentric and kinship worldview or morality or connection through language, only because we've lost it.

D. Firth Griffith: 44:03

Right, your story illustrates my brief, little you know intro to Sequoia, our three-year-old.

D. Firth Griffith: 44:08

It also illustrates this idea that we're born into the understanding that our life matters, because all life matters, and then, for some reason, we unlearn that and it seems to me like it's to some degree outside of us, maybe initially right, that lets us taste it, and then it's also this continual perpetuation of losing responsibility for actions.

D. Firth Griffith: 44:33

If I don't have to see life in the death, I don't have to see life in the food, and if I don't have to see life in the food, I don't have to care what kind of food it is and I can live my life according to my own personal pleasures and desires, and so to some degree it's being reawakened to the sense that not only do you matter because I think in animacy we have the ability to think that, like humans now don't matter, right, if trees are animate, humans are less cool, but it's like no way, whoa, like you are actually more cool because the life that you are is also shared by the tree you matter, um, but we don't have to remember that if it's just a cool woo, woo, a new age idea that exists out there in harmonies, you know, gathering ways, harvest classes that I don't have to participate with.

Harmony Cronin: 45:19

Yeah, absolutely yeah. And I'm reminded too how, even after sort of walking into this life way of trying really hard to be in relation with the ones around us and still being a forgetful human, that it seems to me if I don't, you know, I try in my life to have the consequences of my life be displayed around my home so that I'm reminded. And I think it's part of this disconnection process that happens when we outsource our consequences all over the planet. And that's really simple, right, we poop into the water, the water flushes it away, the trash goes in the magic box and it goes away. And we're getting away. And we're getting our clothing, we're getting our daily needs met from all these different sources all over the planet and we don't see the consequences of it.

Harmony Cronin: 46:23

And so, as much as I can in my life recently, you know, it's like I like cutting down the trees around my area for like building my shed, for instance, and then I see the stump right outside my home where the tree was and it's to remind me like, oh, I did that I have an obligation. What about those birds that had their nest in that tree that's no longer standing, that's now my woodshed, and what about all of the insects and the mycelium and the lichen, and right all of the things on this one single tree that I cut down. And so I like having those, those consequences right in front of me just to help keep me aligned, because if it's not, if I'm not reminded, I will just kind of get back into modern human mode and continue on my day and do whatever and maybe forget to say thanks, forget to just have a pause in the day, to that bird family whose home I destroyed. And that's just such a minuscule thing, it's like one pole in one woodshed. And so multiply that by every decision we're making and all the things that we're using every day, and it is overwhelming.

Harmony Cronin: 47:39

And I can understand that human are. I think our human capacities are, um, quite limited, and they're supposed to be quite limited because we're supposed to be, um, cared for and caring for the land directly around us. I think that's what our, our mind is made for, is like this scale of human relations, and so now that it's multiplied by the planet and we're all of the things coming from everywhere, I don't know if we can actually hold all of those stories, and so of course it feels scary and overwhelming, um, and it's not a reason to shut it off either.

D. Firth Griffith: 48:16

Yeah, this is. There's so much here. Um, well, let's just start with the idea of consequences. Yeah, it's like the othering, like the modernity allows us to to create this other, regardless of what it is. Um, I think so much is bound up. You know, in so many of these modern narratives even with good intentions, narratives with good intentions, they're still bound up in this othering that we can utilize what we can't see to heal what we can, but without understanding the effects of what we can't see in that extractive relationship.

D. Firth Griffith: 48:49

you know, all of these things, that that is really interesting, because you're right, it grounds you to place and as, grounded to place, you're able to have a relationship with the life that your life touches right to the tree. You know and people live in these stick built. You know homes and things and the lumber comes from someone known location to someone loan. You know lonely forest Like, for instance, recently, the state of Virginia, I think, yeah, I think it was, yeah, I think, our home state of Virginia. Here there's more land under monoculture pine than agriculture today. Here, or at least it's almost, it's equal or surpassing, which is an unbelievable statement, simply unbelievable.

D. Firth Griffith: 49:33

But to some very large degree it's not because of the machine. I think that is a metaphor that has been beaten to death and it shouldn't maybe have ever even arisen, because now we're able to like other, like the thing that's grinding our lives to a pulp is this other thing called a machine that we can't touch, neither can we understand. So it's like just emasculating the otherness and the other idea, but like the delimiting, the deplaceness, the ungroundedness. Our neighbor owns many thousands of acres and they just deforested 2,500 acres and it took them three weeks to do it right. And so the pace you know.

D. Firth Griffith: 50:10

But that pace is destroying. But you have a knife in your hand right and it takes time. The harvest takes time, but you bring out a bandsaw and you bring out a knock chamber and you start bringing out, you know, all of this modernized machinery that occupies so much of the harvest process today and and I feel like I'm in a logger logging you know a feller, you know timber feller and I'm just zip, zip, zip, zip, zip trees falling in front of me. But you and I walk out to the woods with a crosscut saw and there's conversations and there's quietness and we actually get to meet the birds that live in the tree and we get to give thanks to it and acknowledge it, and there's.

Harmony Cronin: 50:43

so my point is this this de-scaling of our life seems to, as you say, simultaneously occupy the idea of animacy, and maybe that's what we're afraid of too, is this is not just the responsibility of actually acknowledging the animacy, but the descaling, the, the limiting of our very omnipresent and god-like modern lives back into our animalistic, mammal senses again yeah, right, yeah, and what, what shifts, what very real shifts would have to happen, that, like in our daily lives to allow that de-centering, like, for instance, now I'm thinking about the buffalo who I love so dearly and have a deep, kindred relationship with outside of Yellowstone, and the buffalo are protected within Yellowstone, but then they're not really allowed to migrate outside of Yellowstone, even though they want to and it makes sense for them to. Um and it's something I've thought about for years and have friends working in multiple levels of this issue trying to get more habitat for them, um, and even that term that just coming out of my mouth just makes me cringe Like as if we need to create habitat like the. The earth is their habitat, you know, it's just like, well, the whole idea of managing them like that, um, but yeah, what, we, what? What would have to happen for buffalo to be able to migrate is way less cars, because cars and buffalo don't mix on the roads and so like, would I be willing to not drive as much so that the Buffalo could have the right away on the roads? I think, yes, you know, but those kinds of like big cultural shifts, like we're not talking like reusable shopping bag scale. We're talking like these, like enormous, um, lifeway changes that I think are super crucial and, honestly, most of these lifeway changes, I think, come from the animals themselves.

Harmony Cronin: 53:01

Like, I see the buffalo as so generous. They're so generous what they do for the land, how they create habitat. Talk about creating habitat. Buffalo create habitat for so many other beings, just in their daily lives and how they are and who they are, and they give of themselves to all of the creatures, including the humans.

Harmony Cronin: 53:25

They're so generous and so what if we were that generous, right? What if we look to them as teachers for how to be in service to them? Generous, right? What if we look to them as teachers for how to be in service to them, which is their generosity and sharing the landscape? And so it's. It's interesting that, like, I feel like it's a lot of these kind of um, I see a lot of like uh, folks with PhDs in like management and eco I don't even have the words, I've never been to college, you know but these ways of managing or of being in relation with the world and like the plants and the animals, and I'm like it's. I think it might be a lot simpler. It might just be like asking them what they need, you know, and then doing it.

D. Firth Griffith: 54:19

You're. So, yes, you're. Yeah, I want to jump through the screen and just like embrace you, which is why I'm stuttering, because it's just, you know I I'm in the middle of writing a book, with some indigenous mentors and elders that surround me and just playing with a lot of thoughts and, um, I tell my wife every day you know cause I write in the mornings and I write really early. I love watching the sunrise and my little writing shed that we built here just faces East as a little window, and I watch the sunrise and it's it's the habit of my life, it's the daily ceremony that that grounds me to some degree, because in the rest of life I kind of feel like all I'm doing is punching modernity out in some boxing match that I'm trying to defend.

Harmony Cronin: 54:56

Some whack-a-mole.

D. Firth Griffith: 54:57

Exactly some whack-a-mole, but in the morning, when everything is silent and sleeping, it's like that which life is just comes intuitively, innately, because the rest of the world is asleep. Well, anyways, I digress, but I tell my wife every morning I say, morgan, when I experienced the indigenous worldview or the wisdom held in place by these peoples for thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of years, their message is so simple and it is so simple that we are able to neglect it. And I wonder if that's the point. Because then you open up all of these ecology books and all of these, you know, meta crisis thinkers. You know, like I'm sitting next to this book.

D. Firth Griffith: 55:34

Part of the book that I'm writing isn't to some degree in contest to this book, and so I've read it many times, but it's like an 800, 800 page master book, you know, and all of these thoughts, and it's like this person is so much smarter than you and I, but their life and that which they're pitching is so complicated, it's so bloody complicated, it doesn't make any sense. And then you listen to, you know, a good friend of mine, Shaleta Zaney. She's been on the podcast. She's coming out to do a tree festival and earth medicine gathering in November here and she'll just look at you and she'll be like, oh, you just need a hug from auntie, that's what you need, you know. And it's like, yeah, yeah, one hug would have saved this guy 800 pages. I'm pretty sure that's true. It's just so bloody, you know, it's so bloody simple. If you, if you ever get to meet you later, you will, you will, you will, yeah, you'll, you'll experience the little bit of joy that she just gave to us in person.

D. Firth Griffith: 56:34

But okay, so, like again, you know all of this is so complex and I think a lot of people can listen to this conversation and get so caught up in the overbearing weight to our very modern bodies and souls. Bodies and souls, these souls that clad in clay that we're also told is not clay anymore. It's some, you know, chemically infused toxic. You know, meat suit of shit to some large degree. You know, people get all bound up in it, you know, and they listen to this conversation and you know I get questions a lot, as I'm sure you get questions a lot Like, okay, so like, what do you want us to do?

D. Firth Griffith: 57:12

Like, give up whatever it is. And then, like you were illustrating, you turned this more. You know, centrally indigenous, ancient, place-based wisdom that is in and around all of us but held in a modern sense by the sum of us, and it's so bloody simple. And so what I want to do now, maybe, is kind of step into a new aspect of the conversation. Maybe we can talk about Buffalo Bridge, maybe we can talk about gathering ways, maybe we can talk about your sub stack or what you're playing with in your mind and your soul right now. But how do we start?

D. Firth Griffith: 57:46

People like you and myself, who to some degree you know, I love that you're an animistic Viking, my wife is Viking and Irish. I'm basically full Irish and so we're very similar, you know, you and I, but to some degree we're like these bridgers that are trying to build a communal pathway between where people are and maybe a new state, which is not the final state, of course, but to reawaken dreams, to allow them access into the deeper, channeled, metamorphosizing pathways of death and rebirth and all of these things. How do we start with this bridging process? What's important? Why does it matter? There's a lot of questions there, but I leave it open how you want to address that matter.

Harmony Cronin: 58:34

There's a lot of questions there, but I leave it open how you want to address that. Yeah, good questions. I'm hearing one of my elders now she's dead. She went by the name Phoenicia Medrano, or Tranny Granny, as a lot of us knew her, and she was an amazing woman and she lived on horseback for many years tending to some of the wild food for lack of a better term gardens of indigenous folks of you know, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Um and she really tended these, these places, very, very well on horseback for a long time and she was an old, mad Irish poet, mystic. She was wonderful. So I'm hearing her now and she's saying it's not working out unless it's working out for everyone.

Harmony Cronin: 59:32

And I think it's that simple. Why is it important? Because this life way isn't working out for everyone. It's working out for a very select few of the humans, not even all the humans, Right, and it's not actually working. So I think that's why it's important is okay then.

Harmony Cronin: 59:57

Well, what works? What does work even mean? And I think that if everyone is included, including the predators, the rattlesnakes, the black widows, the cougars, the wolves, the mycelium, all of these beings elves, the mycelium, all of these beings if everyone is included, it's more likely to work for everyone. First of all, I don't think a system can work unless everybody is present. But also, yeah, like, how can we align what we're doing with our daily lives so that it so that everyone is cared for, so that everyone's daily lives are well and Right? It can seem so complicated. I mean, you could just you could write your whole PhD thesis, multiples, on what to do, and I'm sure so many people are doing that right now, so many people are doing that right now. But I think that the distillation that I've come to is how you get your daily needs met, so how you clothe yourself, feed yourself, warm yourself and shelter yourself right the simple human things that we need to be alive. If we can tend to those things without or by minimizing because even me, I'm still relying on the empire, even though I'm trying so hard to figure out how not to rely on the empire, but I still am but if we can minimize our reliance on the empire and of outsourcing all these things, um, and using like ghost slaves in other countries and, um, so if we can take care of our daily needs, I think that that's where the healing really happens, and I experienced that, you know, as a recovering activist.

Harmony Cronin: 1:01:56

Once I realized that I was so angry because I didn't know how to take care of myself without relying on the systems that I didn't agree with. And so, like, let's keep it simple. Like, how do you feed yourself? You know, how are, yeah, when are you getting your clothes from? And not, I mean, I'm wearing like clothes from the thrift store, but also deer skin, you know. And so if we can like simplify it, it doesn't have to be these massive global solutions. It can be like very small in you and your community or your family and the dirt right outside of your door, Um, and we're so much more well and balanced and healthy when we scale it down like that too.

Harmony Cronin: 1:02:44

I think getting obsessed with the big global, complicated solutions just really devours your soul. I mean, I experienced that as an activist. I wanted to save the world and I thought I knew how. And you know, I banged my head against the castle door for years before I decided to walk away. And I'm still recovering from that. And like the grief and the speaking out loud to plants and animals and asking them what they need and we're capable of it, Like you can do that. It's not. You don't need a PhD, Right.

D. Firth Griffith: 1:03:33

Yeah Well, I think, in addition to that, it requires this dismantling.

D. Firth Griffith: 1:03:37

I made a comment earlier that the dismantling is not important as the remembering, but I think at this moment, maybe the dismantling is more important, at least in this case.

D. Firth Griffith: 1:03:49

If we are concerned with the saving of the world, I think we will always miss the plant that needs a relationship at our feet.

D. Firth Griffith: 1:03:59

I think that's the danger of this metacrisis narrative. It's not that maybe, and again, there's layers of this, and so I don't want to sound too contradictory, because all of the layers matter. But to me, the most simplest moment in this narrative is that when we are concerned with something so much larger than ourselves that, like you said earlier, I don't even know if we have the capacity to understand and maybe we shouldn't ever try to escalate that capacity we miss the life around us, right? So, for instance, in like the agricultural narrative, we need to build soil and increase biodiversity, while we don't respect the weed, right, the dandelion that's trying to feed us and all of the wonderful things that dandelion and its leaves and its flowers and its pollen and its roots and everything else is trying to nourish with us, and have that conversation right at our feet because we're concerned about the soil health in the field that we've totally disrespected anyways, and so, to some degree, what you're saying is a coming inward again through dismantling that which we thought was our body.

Harmony Cronin: 1:05:02

Yeah, yeah, that's right. Yeah, I do think that some deconstruction is really important. Um, because and this is something granny taught us a lot about is, um, a lot of folks will start getting into movements like rewilding, um, or primitive skills with them, and that, though you think you're doing something different, you're not actually, because you're still taking this taker mindset into it. And she would talk about, like foraging wild foods, for instance, and how we think, oh well, yeah, instead of buying groceries, we'll go forage wild foods. But if we're, if we haven't deconstructed and really it's not like, oh, I deconstructed my inner colonialists and now I'm done it's like you have to. I'm still constantly like, wow, I'm still carrying that belief. I ha, it's like you have to keep it, keep working at it. Right, I think of the word balance, like to be in balance is not a state of rest. Actually, if you're balancing, you're always making micro adjustments and so, right, with like decolonialism, deconstructionism, work, yeah, you're constantly working at it. Um, cause I was brainwashed for I mean, the better part of 30 years or whatever, so it's really deep in there.

Harmony Cronin: 1:06:31

Um, so, with harvesting wild foods, like, right, a lot of folks will just go to the forest now, or the wild flowers, with that same taker mindset as if it's the grocery store and they'll just take and take and take and take and take back, physically planting back and like physically planting wild foods before ever harvesting. First of all, as a way of that reciprocity that we were speaking about before, um. And so the deconstruction right is so important, um, while also the remembering too, because you can't just deconstruct into I mean, you can, you can deconstruct just into a blob of, you know, guilty self-hatred, whatever, um, but that's not really helping anything either. And I do think that we're supposed to be a keystone species and so right, learning, learning how to really question the impulses that arise in us for how we want to participate in the world, and probably working in direct opposition to the instincts that we think are instincts but that are actually conditioning Um.

Harmony Cronin: 1:07:58

And so, just like a simple example of this that I can think of with granny, with Phoenicia, is, you know, okay, we're at a gathering, a primitive skills gathering, there's 300 people there and she gets up and she says how many of you guys have ever harvested wild berries before? And you know, everybody raises their hand, they're feeling all proud of themselves. They're like, yep me, I totally I'm a wild crafter, you know. And she's like how many of you motherfuckers have ever planted a wild berry, bush, and nobody raised their hands Right. And it hit me of like, oh shit, oh shit, you know, of course, like nobody taught us that we're like escaping some system as, like these refugees, like getting away from this, like empirical domination system, but unless somebody says, hey, you know, you should plant that seed, like physically plant the seed, or lay in the canes right, that's something she taught us is like lay in the all the cane berries, like clone them out, then, of course, we're just going to be operating from our same conditioning Um, operating from our same conditioning Um, right, so that work is important. And then having something to rebuild yourself with um is also really important, because I see so many folks get paralyzed with the guilt, the guilty consciousness and not knowing what to do, and especially folks that look like me and you, you know um feeling like maybe we don't, we are not um deserving of place-based life way, um, because we were settlers here, you know. And so I think that a lot of those kinds of feelings can be valid and like an important stepping stone um to awaken to yeah, what we have inherited, which I'm a beneficiary of cultural genocide, that's real, I am a beneficiary of that. So what am I going to do with that? And that informs a lot of my work. But also, right, our ancestors were place-based, are place-based and had life ways that were in direct communication with the ones around them for a long time.

Harmony Cronin: 1:10:36

And many things happen to us. All sorts of things happen to us and those stories you can trace in your own ancestry, going back and back, and it's often pretty horrific and heartbreaking and full of like immense grief. And I'm thinking about right now. You know I went on an ancestral pilgrimage to England and the Isle of man in Ireland a couple years ago because that's where some of my people hail from, and I was camping in the hedgerows of England, hitchhiking around, and the ghosts of the wolves and the bears are still in those forests and the forest is longing for the wolves and the bears.

Harmony Cronin: 1:11:25

The hole that was left when those animals were killed to extinction is so raw still, even though I think it was hundreds of years ago that the wolves and the bears were wiped out, but I can still feel the forest literally weeping for them and you can kind of glimpse the wolves still like running in the undergrowth, you know, and the bears lumbering through, and and I think that it's really important for us to realize okay, well, what did our ancestors do? My ancestors in England wiped those animals out, and so what are the direct consequences of that for everyone involved over there? And let's not do the same fucking thing over here. You know, let us learn from our, our inheritances, and now let us do something different.

D. Firth Griffith: 1:12:20

Yeah, yeah, well, a good friend of mine is a laglala lakota pipe carrier and he talks quite a bit about the idea of remembrance. That, uh, so much of place-based wisdom is this capacity to remember, not the perfection of life, but the capacity to remember, and I think that's what you're well describing. There is that this idea of living in kinship is innate within all of us. Maybe it's sleeping in some of us more than others, or others more than some of us, but it's. I mean, going back to dreams again, like I mentioned earlier, this idea of memory and dreams. You and I have dreams that we dream backwards. Right, we are ancestors to some very large degree, and we have to reconcile that and grieve that and also rejoice in that. There's all of that there. And then, at the same time, how can we dream forward? What sort of legacy can we actually now writ, you know, right into the landscape, you know, and so it's an active participation?

D. Firth Griffith: 1:13:22

But but I think and I want to get your opinion on this what calls to me and in conversations like this, is the idea of time, because so much of the narrative that surrounds you and I is that we only have so much time. Technocracy is eating its way from the outside. Globalism or climate change or desertification, is eating its way from the inside out and we're compressed between these two innate narratives of this machine grinding the world and we have to do something now. This is activism. We have to stand up, we have to fight this, we have to change all of these very big things and we only have so many left, so much time left. In agriculture, we see the mythos of 60 harvests. We've been beaten over our heads that industrial agriculture is depleting the land. Of course it is Duh. It's like an aha moment. It's just like wow, when you abuse a tree, it stops talking to you. Imagine that, like you said earlier.

D. Firth Griffith: 1:14:19

But this memory dreaming both forward and backwards, it seems that the time, not only that we spend doing this is the idea that matters, but also the time it's going to take to truly remember is not the time that you and I are going to occupy. I don't believe, and that's not the point, even if it is right. Even if you and I are going to occupy, I don't believe and that's not the point, even if it is right Even if you and I can come to a complete, reawakened sense of our consciousness where we have full autonomous and intrinsic capacity to truly be a wonderful kin in our environment. Even if that was possible, getting to that point as fast as possible doesn't seem to be the point. That's what I'm saying. What do you think? How do you think time plays in all of this?

Harmony Cronin: 1:15:05

Well, I don't believe in linear time. To start with, I think that that was something we were indoctrinated into that isn't actually real, something we were indoctrinated into that isn't actually real. And so it is interesting if time is not linear and it's something else and the past and the future and the present all are a lot more intermingled than we think they are. Yeah, it's not Uh-huh. Okay, right, so this idea that you're kind of proposing of like, oh, we need to hurry up and become more concentric as fast as possible, or whatever, that's still kind of growing out of the productivity mindset, right, it's still kind of growing out of that conditioning of dominant culture of you're supposed to optimize everything to its fullest potential as quickly as possible to optimize profits, and that's just not the way the real world works, the real world being like not dominant culture world. You know the opposite of how that term is usually used like not dominant culture world. You know the opposite of how that term is usually used.

Harmony Cronin: 1:16:23

So, right, yeah, and I think you're, I think you're onto something that is. That's not the point either, in that, yeah, to slow down would be like what I mentioned earlier. What we think of as instinct is often just conditioning and so like kind of doing the opposite of what your impulse would be to do, which is like, yeah, hurry up, and like we got to save everything. So we got to like get on it, cause we're going to all go extinct in three years or whatever it is the latest kind of doomsday prophecies are saying, which might be true I'm not saying they're not true, but it's still rooted in the same behaviors that got us here in the first place, right? So let's try something different.

D. Firth Griffith: 1:17:10

Just when you say it, you know it's just like. You know I love, I love, I do this podcast for this, for the sole reason of having conversations, just happens to be recorded and it happens to be an excuse to do it, and so I hope people are along with us and I hope people listen and I hope people enjoy it and laugh with us. But, like in the moment you know that you and I are sharing in this space, I feel like all you can do is just laugh when you start to actually hear the challenges presented against it. You know, like well, no, daniel, soil health matters, yeah, of course. Like so does everything else? Your feet trample and it's going to take you a long time to get through that. And again, not this idea of linear time, but, like you know, I love talking about the idea that.

D. Firth Griffith: 1:18:00

You know, a lot of people want to come out to our harvest court classes and sometimes it doesn't make sense for them. They can't travel, they can't get away, whatever it is. And I ask them, I say, well, do you intend to come at some point? And they say yeah and I say say then you've already come. Start living like you've come, because you have. It's just not in your experienced reality yet. You know, and if we started to actually think like that, how much health could imbue the lives and the communities in which those lives occupy. So much more. I don't want to say faster, but so much more effectively, sooner, right, like the healing that comes when you already believe that you can be healed, that sort of idea. Yeah.

Harmony Cronin: 1:18:46

Yeah, oh, I love that. Yeah, right, I say something similar when I have students sign up for our harvest classes. You know, I say, okay, you're walking towards it even now and you've been walking towards it the whole time and so, yeah, act accordingly, proceed accordingly. You know, yeah, it's not something off, way off in the future that you'll get to like you're in it now, yeah, even just writing the email of, to like you're in it now, yeah, even just writing the email of I want to sign up, okay, yeah, so who were your ancestors? How were they with sheep? How did they tend to their flocks? What did they do? What kind of ancestral dishes did they make out of sheep meat? Like, do it now because it's, it's like right.

Harmony Cronin: 1:19:30

Also, I've been told that, um, there is no actual beginning to a ceremony, right, it's always begun and so we're in that time it's. It is interesting that I think that in modern culture we are, we kind of have this way of thinking about, yeah, things as the checklist to do of like, okay, the slaughter class is coming up, but like my life is disconnected until I do it, and then I'll have it checked off and then I can be different kind of thing Right. So I kind of see what you're saying there of this like, yeah, already act as if you've done it, integrate that, and it's not right. I don't own this knowledge either. I'm not the one, I'm not some like special person by any means, and everybody is capable of doing what I do. For sure, it's not like I was in imbued with some special spark from the gods. You know, um, though I think we all are. But I'm not saying that, not saying yeah, like I'm not some gatekeeper that you have to go through in order to be different in your life.

D. Firth Griffith: 1:20:43

Just go talk to the sheep well, I just bringing the conversation, you know, full circle to how it began with this idea of bios and describing yourself on paper and in in such a small and disoriented and distracted way. It just seems like that that's really the, the thread that is woven so ungently through this very ugly fabric of modern life. Because if you aren't somebody special, if you, if you don't have the gate and the key to the gate and you're not standing there as this unbelievable, you know transforming force of a person that ushers people from a previous day to a new, like then you're just harmony, you know, and you're the birds and the trees and the pacific northwest that flows through your veins as water and blood and the mute, the beautiful, you know mixture of the two. Like that's who you are. You know when, when, when you do escape from the narrative of no, no, no, I'm a climate solver, you know I am, I am activating, you know, so much of my intrinsic and purely animate and intelligent wisdom to heal. Or like when you're not this big, wonderfully bad thing, and I say that either both, either negatively or positively.

D. Firth Griffith: 1:21:59