“When evening has come, I return to my house and go into my study. At the door I take off my clothes of the day, covered with mud and mire, and I put on my regal and courtly garments; and decently reclothed, I enter the ancient courts of ancient man, where, received by them lovingly, I feed on the food that alone is mine and that I was born for. There I am not ashamed to speak with them and to ask them the reason for their actions; and they in their humanity reply to me. And for the space of four hours I feel no boredom, I forget every pain, I do not fear poverty, death does not frighten me. I deliver myself entirely to them.”

- Niccolò Machiavelli

Hello readers! It is time for the first installment, which I anticipate becoming a weekly or twice-monthly parlor, or salon, where we can discuss the books and other Substacks we are reading, or really anything else you want, whatever is on your mind.

I’ll start. Here are a few things I have been reading lately.

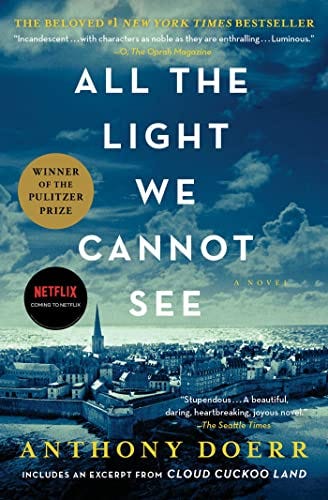

NOVEL: I devoured, like blueberries, that is: small bit by small bit but bowls of bits nonetheless, Anthony Doerr’s Pulitzer Price Winning novel, All The Lights We Cannot See. It is a substantial novel, 500 pages, but conveyed in short chapters of no more than 2 or 3 pages. Novels have always been quite difficult for me, perhaps for the same reason that I have eternally struggled with movies. Sustained attention to a given subject is not a hard thing for me to conjure the ability for, but rather my failing is due to a lack of appetite. I doubt this is a virtue but it is true, nonetheless. James Joyce is a fine example—wonderful, lyrical prose that stir the soul but his plots (or lack of plot) gets me. Like Thoreau, this may be my library, but my “study is out of doors.”

But Doerr’s work punctured my palate at once and never let me go.“The face of a grand building rises gracefully, pilastered and crenelated. Stately wings soar on either side, somehow both heavy and light. It strikes Werner just then as wondrously futile to build splendid buildings, to make music, to sing songs, to print huge books full of colorful birds in the face of the seismic, engulfing indifference of the world—what pretensions humans have! Why bother to make music when the silence and wind are so much larger? Why light lamps when the darkness will inevitably snuff them?”

This is, to inappropriately reduce a grandly long novel to a singular idea, the central question Doerr’s seems to set out to discuss. Set during World War II in occupied France, the book traces two stories that wonderfully and horridly collide as they converge within the scenes of war—famine, pain, ugliness, greed, fascism, racism but also love, family, community, and what it means to be alive. It is, one of the best novels I have yet read.

If you have read it or when you do, please let me know your thoughts—it would be a blessing to talk with you about it here.

SCIENCE: Elizabeth Kolbert’s work is wonderful for those who seek information but not a change of heart. I mean, in writing about how global human migration and travels directly contributes to habitat loss and species extinctions, Kolbert tells stories of how she flew all over the world to meet with people and scientists on the leading edge of “saving the world.” That said, Kolbert’s The Six Extinction is chock full of information concerning the finer and often hard to observe aspects of modern extinction events happening, often, right under our noses. The book traces a number of surprising extinctions and then concludes with some important considerations if our children and grandchildren are to laugh at jumping frogs, climb the ash tree, or marvel at migrating birds.

Kolbert describes what she terms, “The New Pangea,” that is the Earth’s biota is experiencing a remixing, a “mass invasion event.”“During any given twenty-four hour period, it is estimated that ten thousand different species are being moved around the world just in ballast water, Thus, a single supertanker (or, for that matter, a jet passenger) can undo millions of years of geographic separation.”

Species evolve in communities, but these communities are not in co-creation with all other communities given the separation of time, space, geography, and, in this way, evolution becomes, often, isolationist. This is changing as humanity and our capital systems become more and more global. What interested me deeply about this book is the inevitable mathematical-ness of the problem—as humanity becomes more global, the globe’s life becomes less diverse; as the globe’s life becomes less diverse, humanity becomes more global in the name of relationship and cross-national co-creation. We see this as thought leaders in the saving the climate space who fly around in jets to speak at international consortiums and conferences concerned with biodiversity loss. Interesting…

SUBSTACK: Carly Wright’s

has blessed me recently with deeply thoughtful writing about her deeply thoughtful life among sheep and goats in the West Cork mountains. Beautifully wild landscapes meet beautifully wild writing. Her recent piece, Tiny Ruby, is a moving tale of the limits and joys of living life, fully and painfully, among the world in and around our bones. I encourage you deeply, take a look and subscribe!

SCIENCE: For a book that I am finishing up writing this winter I have been studying genetics and the role that genetic sequencing has and is playing in the understanding of human migrations and creation stories. Strange to call it a page-turner, Svante Paabo’s Neanderthal Man captivated my attention throughout—its science and its story. Paabo, the founder of paleogenetics, first sequenced the Neanderthal genome in 2010 and the book details his many ups and downs, successes and failures during the process.

I read Ronald Wright’s A Short History of Progress earlier this year and was struck by the competitive nature that modern and streamline cultural critics (intellectual onastics, I call them) hold in regard to the human species. Wright argues that progress and its inevitable “traps” or ailments are innate in the human DNA and this is perceptible from our beginnings—from Homo sapiens first colonization and genocide over the Neanderthals to modern modes of energy and industrial capitalism. Modern humans killed the Neanderthals, Wright holds, and caused their extinctions. But, by 2019, Paabo’s team concluded that all living humans today share between 2 and 5% of their genome with Neanderthals. Crazier yet, we share Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) with them, meaning long-term relational breeding between our two species.

In my recent book, Dark Cloud Country, I wrote that “Science is like good friends who know what the other thinks but often gets it wrong.” That, to some large degree, is largely true. But, in this case, Paabo’s genomic research and sequencing has proved that ancient humans were, in fact, good friends who knew what the others thought and got it right. They relationally lived together, evolved together, and co-created with one another. Riveting to think their blood flows through our veins (or is it our blood and their veins?)

Okay, that is enough for now. Plenty more books to discuss in the future—but I hope you find something here of interest, to discuss.